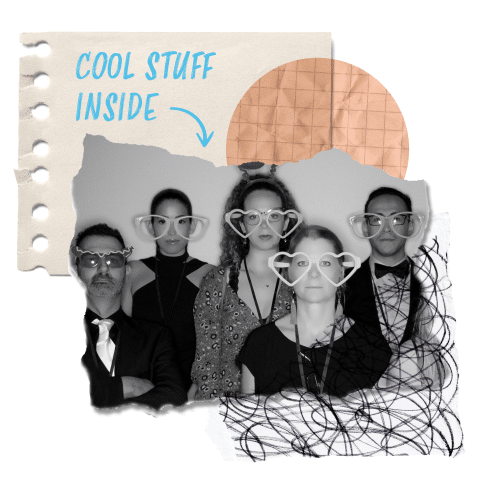

Above photo: Documentation from The Celilo Wy-Am Salmon Feast in 2015, a weekend-long Pow-Wow at Warm Springs Indian Reservation. Photo Credit: Alyssa Macy / Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs

A big part of our job as social justice communicators is to have the humility to admit when we miss the mark. One of the biggest misses comes from environmentalism: it’s the failure to recognize that our work must always begin and end with tribal sovereignty.

Our agency cut our teeth working in and learning from the environmental justice movement. We’re not beyond admitting that our own progressive environmentalist logic and mindset, while well-intentioned, was at times unwittingly perpetuating the very same white supremacist culture we strive to undo every day.

We have recently seen that through the eyes of journalists, but also from the environmentalist movement overall. Without respect for tribal sovereignty, however complex our work may be, it will never amount to anything more than the equivalent of a performative land acknowledgment.

For some specifics, here are the top 3 lessons we’ve learned firsthand. We invite journalists (and all storytellers!) to absorb them alongside us:

Top 3 mistakes:

- Not consistently consulting Native communities as sources — much less as experts. When stories do feature Native communities, their voices are included only briefly, most often to demonstrate how marginalized they are. But many Native communities are advancing climate solutions with deep scientific and cultural expertise, built over thousands of years. Reporters either fail to recognize this at all, or downplay it to make room for the perspectives of (majority white, moneyed) environmental nonprofits and state governments.

- Did you know?

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples specifically acknowledges “that respect for indigenous knowledge, cultures and traditional practices contributes to sustainable and equitable development and proper management of the environment.” As a signatory, the United States has committed to uphold this international standard in its own decisionmaking. Take a peek at how the Biden Administration puts the commitment into action.

- Did you know?

- Failing to respect cultural norms. Each community has different ways of processing requests for interviews or commentary. For example, one of our clients has a very deliberate process to decide who should be quoted on behalf of the entire Tribe and how they should speak about an issue. But when reporters reach out for comment, they tend to expect a response within a day. When sources aren’t able to meet that deadline, instead of learning about and adapting to the cultural norms of the people they are asking for comment, reporters simply lament their “inaccessibility.”

- Talking about tribes interchangeably. Not all tribes have the same challenges, environments, cultures, levels of wealth, government structures, political influence and relationship with state and federal governments. Every tribe’s situation and approach to their environment is distinct, yet reporters fail to treat it that way.

What to do differently:

- Understand that when you interact with a tribe, you interact with a sovereign government. It’s common for non-Native people to think of tribes like a membership group with some limited political power, or as something that existed in the past. Before you reach out, do your research to answer these questions: What does tribal sovereignty mean? What treaties and governmental structures do tribes have in the state where your story is situated? Appreciate the immense complexity of the political landscape they exist within, and the uniqueness of their histories.

- Build a real relationship. A lot of these mistakes would be avoided if reporters had more relationships with tribes. Sit down for a conversation — outside of a story — about how best to work together and how best to understand an issue.

- Be humble. Writer and teacher Carleigh Baker said it best: “For environmentalism to stop perpetuating colonialism, white allies must be prepared to self-critique and learn from colonial histories.” We’re so used to propaganda from climate deniers and people who want to burn the world for profit, that environmental reporters develop an inherent skepticism to any viewpoint that does not fit the mainstream green dogma. You must acknowledge that your perspective may not be the full story. It denies you the opportunity to listen to people who may know the truth of the land longer than you ever could. Native communities have been here, with intentional and effective land management practices, for far longer than you or the environmental movement has ever existed.